|

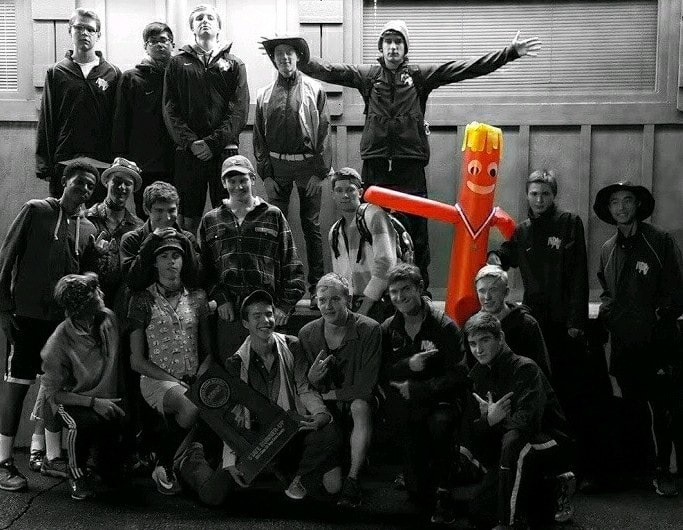

It’s a long-time NXC tradition the night before the State Meet to gather the top 12 for a meeting before bed. We never talk about the race or strategy; it’s instead evolved over the years as a time to reflect on the journey, to speak frankly about the distance we’ve traveled and how it has changed us, to pause before the bedlam and acknowledge our good fortune and shared sacrifice. Sometimes these meetings are thoughtful and sincere, and sometimes they dissolve into fits of silliness, but they invariably reveal the character of the team hours before it’s put to the test. And so on November 3rd, 2017, we assembled—seven seniors, five juniors, and five coaches—in a hotel meeting room. At first, the athletes were quiet; many had never been in this meeting before and were unsure how to speak. “What are you most proud of?” we asked. There certainly were a number of highlights to choose from the past several seasons—Michael O’Connor’s stunning ascension, Keanan Ginell’s stubborn tenacity, or Chris Keeley’s canny maneuvering. Instead, they talked about traffic cones. Well, one traffic cone in particular. The seniors told a story where they snatched the orange rubber marker from a construction zone, then drove off, evading the police for… reasons? It was hard to follow the narrative as the storytellers kept dissolving into fits of laughter. Then they told a story about tricking Keeley into believing he was being stalked by a clown. Then a story about sneaking through a park forest. Again and again, the memories they returned to involved not running, but teenage shenanigans, friends joined in capers. For the record, no one condones theft or clown impersonations. But there aren’t many adults who don’t have a story about getting away with something. And suddenly, it made sense why a room full of runners would swap stories about chicanery. As athletes, we train our bodies to be strong, swift, tough, and methodical. But the real battle is between the ears, a struggle against the forces of doubt. To win, one must convince himself that he is not a fraud, that he belongs on a podium. That it’s not a trick. These athletes were trained in the shadow of Dan Weiss and Michael Widmann, Connor Horn, Jake McEneaney and Jackson Jett and Matthew Milostan. Athletes whose names sit in trophy cases, whose achievements are recited as proof of the investment in training and devotion to excellence. To join them, each of the top 12 had to overcome their own qualms and skepticism, their own sense of fear and inadequacy. They had to convince themselves, in effect, that they weren’t ‘getting one over.’ Perhaps the thing we’re most proud of in 2017 is how each of these men made that journey. These are their stories. Quentin Quagliano, senior: In his own way, Quinton has often been on the outside looking in. Once a stalwart soldier whose times dipped into the low 16s as a sophomore, he was hamstrung for seasons on end by injury. Rather than despair at his misfortune, Quinton took this period to expand himself, developing interests away from running. His growth sometimes strained his ties to his teammates, a problem compounded by Quinton’s forthright manner. Yet it also led Quinton to grow in confidence and self-assurance, qualities that gave him extra strength during his senior campaign. Quentin didn’t have a bad race in 2017, a season whose highlights included his first place finish in the Open Race at Culver. He raced like a dog refusing to surrender a bone; no matter how heated the fracas or how insistent the pace, Quinton stuck to the leaders of the JV Race at Richard Spring, Twilight, and the DVC Conference Meet. In a way, this stubbornness doubled as an assertion of his selfhood, an identity he had pursued sometimes on his own, but always in accordance with our team’s values and goals. I am Quinton Quagliano, said his races. I will not back down. And I belong. Matt Jett, junior: Now and forever, there will only be one Jackson Jett when it comes to NVXC. Of course, that poses a problem for his younger brother, tasked with following the inimitable barely a year after Jackson had shocked the state. How do you live up to a name that has come to mean ‘doing the extraordinary in ways that don’t make any sense?’ For Matt, it has come to mean making as much sense as possible. Where Jackson could be mercurial and insouciant, Matt has been methodical and earnest. His running logs are more thorough than U.S. tax code, and his reflections on his workouts as intricate as an FBI profiler’s. At times, the pressure of such attention to detail could lead to paralysis—where Jackson’s genius (and folly) could be how little he overthought, Matt sometimes suffered from an abundance of concentration. Yet his 2017 season began promisingly, with Matt finishing just seven seconds behind Michael Madiol. All summer, he’d shown greater surety, a more relaxed posture, a more reasonable frame of expectations. When he was felled by injury, we grew concerned that the old Matt would resurface—that he would grow impatient with his recovery, obsessive with missed workouts, disjointed with anxiety. He didn’t. Matt showed self-awareness, growth, and maturity in his recovery. He didn’t rush back. He put in the rehab work. And when his foot was ready, he carefully selected the correct race to return and the best plan for attack. And he executed. The Thursday before State, Matt led a three-mile time trial from gunshot to finishing tape, gapping the field and running an impressive 15:32 all by himself. It was the sort of gutsy race that could only be run by a runner in full command of his body and mind, aware of the challenges of his craft. Matt Jett had overcome more than injury; he had found a new way to be a Jett. Dakota Getty, senior: Dakota ran 19:44 his first season. He was our 19th best freshman at conference. There was nothing distinctive about his presence as an athlete, save for a cool buzzcut mohawk. But like many runners in our program’s history, Dakota slowly began to discover his talent and interest in the sport over the long winter months. His times began to inch down; while former teammates abandoned the grind for other pursuits, Dakota kept plugging away. By the time he was a junior, Dakota was positioning himself near the front of the JV chase pack. This past summer, he clicked off 60-second 400s as part of a team relay workout. Dakota Getty, it would seem, had arrived. Then came the Hornet-Red Devil Invitational. Dakota had a tough race, falling off the lead pack after the first mile and losing himself to the drift. He ran the 16th fastest Neuqua time that day. Every runner knows the feeling of helplessness when a race gets away, but what’s worse are the whispered doubts that follow. What if that’s all I am—the flailing, the failure? What if I’ve traveled all these miles, and haven’t moved forward an inch? The story of Dakota’s season—and his high school career—was told two weeks later at the Richard Springs Invitational at Detweiller. On a course that offered no respite from a sweltering sun, Dakota broke from the pack to win the Open Race by more than 10 seconds. He ran 15:58 on Illinois’ most famous course on a day that no one particularly wanted to go fast. Dakota quieted his whispers, and he became a trusted substitute, swapped into the top 7 at Conference and Regionals to spell runners in need of recovery. Dakota hasn’t worn a mohawk in years. He hasn’t needed it to stand out. As a senior, he found another way. Keanan Ginell, senior: Height is overrated in distance running. Dathan Ritzenhein is 5’8”; Alan Webb is 5’9”. The taller the man, the heavier the frame, which wears him down over a longer race. And yet, as any diminutive athlete will admit, it can be dispiriting to line up in a box between Goliaths. Clothes look better on tall people; they have more fun at swimming pools; they have less trouble changing light bulbs. Between Dakota Getty, Tyler Bombacino, Alex Johnson, and Danny Winek, the 2017 team was one of our lankiest squads. Standing beside them, Keanan Ginell has always looked small, and it would be easy to overlook him at the starting line. That would be a mistake. In a season defined by the ups and downs of our senior class, Keanan proved the steadiest, flintiest, most reliable competitor (other than Ryan Kennedy). There was never a race where Keanan betrayed doubt or uncertainty—he raced with his fixed straight ahead, his shoulders squared up, his stride confident and relentless. Keanan’s race strategy in every JV race this season was very simple: Win. He pursued this by immediately seizing control of the pace and daring teammates and competitors to match him. When others faded, Keanan surged; when doubt tugged at their calves, Keanan shook it off. He won the JV race at Lockport, finished 2nd at Twilight, 2nd at Conference. He PR’d by 13 seconds at Regionals. On that day, he would have been—at worst—every other teams’ third best runner. Keanan never had much to say about these achievements. He has always been soft-spoken and nonchalant. In the crowded hallways of Neuqua, it is easy to lose track of him. But amidst the hundreds of bodies straining for dominance on Saturday mornings, he’s hard to miss. Keanan Ginell is a giant. Michael O’Connor, junior: Michael O’Connor was buried. During the summer, one of our signature Varsity workouts is to run to a forest preserve three miles from our base, throw in some hill sprints, then tempo back. It can be a brutal, scorching slog, but it reliably teaches discipline, toughness, and grit. And on that day in late June, the Green Valley workout had ground O’Connor to a halt. He had a miserable summer. One year after he’d proved so integral to an ascendant sophomore squad, Michael seemed lost, frustrated, and without answers. Though he never lost his trademark optimism or good cheer, the furnace that had once burned so intensely seemed to have dimmed considerably. But the funny thing about Cross Country races is how a three mile sprint can clarify everything. While some runners excel in workouts precisely because they hold no stakes, there are a few competitors who cannot thrive until the spikes are laced and the bibs are pinned. So it was this season with Michael. He was 43rd at Hornet, then 3rd in the Open Race at Richard Spring. Incredibly, he won the JV Race at Twilight, dropping 40 seconds off his time at Hinsdale. Ten days later, he was the JV Conference Champion. Michael O’Connor wasn’t done. He dropped another 17 seconds to PR at Regionals, then finished 15th in the Waubonsie Valley Sectional, running stride-for-stride with Alex Johnson and Tyler Bombacino, who both beat him by a minute two months earlier. At Sectionals, Michael O’Connor beat 11 other teams’ best runner. He would have qualified for State as an individual. Summer training, of course, is the key to every successful Cross Country season. But greatness doesn’t always show itself by winning the workout. Sometimes a man has to be buried to find out just how remarkable he is at digging. Chris Keeley, junior: One week ago, Chris Keeley had his best race of the season. He finished 7th at Sectionals, finishing seven seconds behind Ryan Kennedy. He was our second man across the line. More importantly, he ran with confidence, canniness, and even a touch of swagger. On Saturday, Chris ran his worst race. It started perfectly—paced by Ryan, the pack came through the mile at exactly the point we’d talked about. Chris was then to move up, to break away and pick up places in the middle of the race, just as he had all season. But this time something was wrong. In the hundreds of variables that go wrong in a race, it’s hard to isolate just one. Maybe his immune system was just a little off. Maybe we waited too long to taper. Maybe it just wasn’t his day. But Chris could feel it, a pebble interfering with a carefully calibrated engine. His mind panicked; his capillaries constricted. It became difficult to get oxygen to his muscles. He entered anaerobic shock. Finally, with about 150 meters to go, Chris Keeley collapsed. Afterwards, everyone told Chris the truth. That the team had only reached this point because of him. That his talent, his dedication, his intensity, his passion had inspired everyone to train, to sacrifice, to believe. That no race—even a first place finish—would have beaten Downers Grove North on that day. That his teammates loved him, that they had his back, that they had carried the load when he had faltered. That his coaches believed in him; that his parents were proud. That he would have another shot next Sunday at NXNs and a year from now as a senior. That one race is not the story of a man; that his name is made of the hundreds of days before hand, where he shows his character through his actions and the causes to which he devotes himself. That State 2017 was a chapter, not the book. All of that was true. And Chris Keeley left Detweiller with a medal around his neck, and a trophy that would one day bear his name. But for ten minutes before the ceremony, Chris lay on the ground alone and wept. This is the hardest lesson to learn, and one we would spare our runners if we could. Sometimes we fail. Sometimes we convince ourselves that victory is possible when it is completely out of our hands. Chris Keeley loved this team so much that his inability to consummate his vision felt like dying. Yet the foundation of every great thing that Chris will ever do—as a husband, a father, and a man—exists in what happened next. For a long time on Saturday, he lay on his back gasping. And then, after a while, Chris Keeley got up. Tyler Bombacino, senior: The ancient Greeks had two words for time: Chronos and Kairos. The former refers to sequential time—the order of minutes, seconds, and hours that make up our day. The latter, however, means the right, critical, or opportune moment. While Chronos is quantitative, Kairos has a qualitative, permanent nature—in the New Testament, it is referred to as the “the time appointed for the purpose of God.” Another way of thinking about it: Chronos keeps moving, but Kairos lasts forever. Runners are instinctively concerned about both. We measure our excellence with Chronos, but determine every race with Kairos. This is a clear way to describe Tyler Bombacino’s senior campaign. He was superbly prepared—fit, seasoned, and determined. A leader in workouts, an exacting presence when it came to commitment and dedication. He had already helped steer a State Championship 4x800 relay team. There were few athletes in our halls more willing to pay the price of victory than Tyler. And yet, he often wears his doubts on his face as plainly as his own eyebrows. Tyler is haunted by the mystery of failed races. What allows him to focus in some clashes and yet drift in others? How is it that some battles come easily to him and others painfully slip away? The uncertainty that exists before the gunshot weighs so heavily on him sometimes that he cannot make eye contact with his coaches. It’s not that he’s mentally weak; it’s that he’s in suspense of Kairos. Saturday’s race started well for him; he paced out the first mile perfectly and charged into the back half practically linking arms with Alex Johnson. And yet in the back half, away from the madness of the crowds, Tyler began to slide. His head dipped, his shoulders lost their composure, and a gap appeared between his teammates. No one knows the truth of what happened yet—perhaps not even Tyler—but what we can say for certain is that somewhere in the last 500 meters he came alive. He began moving—fast, hard, through the field of competitors. He caught up to Alex, charging through the chute like a man on fire. Tyler Bombacino had arrived, in the time appointed for our purpose. As Dave Walters reminded us a few weeks ago, every race has a moment of truth. Runners cannot know until that point if they are worthy of victory, and so many come to dread it. The best thing that can be said of Tyler on Saturday—and for his time at Neuqua—is that when Kairos appeared, he seized it. Alex Johnson, senior: Alex’s teammate, Ryan Kennedy, is an impatient runner. He wants to win early, and so he pushes early. It has been that way since he put on Neuqua’s colors, always in a hurry to make Varsity, the top 12, the State Meet. Alex, on the other hand, is extraordinarily patient. You can tell, watching him warm up—his drills are methodical, his habits practiced. He brings each rep to full completion, lowers every push up all the way to the ground. He is unhurried by the sun or discomfort; he is dedicated to his craft. Alex has overcome injury through this persistence; he has shaken off disappointing finishes because of it as well. As a junior, when Coach Vandersteen suggested the time-consuming process of changing his stride, Alex acquiesced and saw it through. He has run more miles than most, accepting the heavy burden of fatigued legs in races, because he knew that when the time was right, we would pull back on the training, and—like springs freed of a heavy weight—Alex Johnson would explode. His patience was rewarded on Saturday, where Alex finished as our fifth man. He crossed the finish line wobbling unsteadily, his powerful frame completely expended by the effort. As he had all season, Alex provided the steadying presence to ballast the dizzying highs and lows of his fast-twitch teammates. And he had raced—once again—patiently, letting the race come to him before a furious final charge. It was a remarkable conclusion to an indelible high school cross country career. “You know, I never thought I’d be one of those seniors tearing up after it was all over,” he reflected afterwards. “But I see why they do now. It goes by so fast. It doesn’t seem that long ago that we were running around the field as freshmen, and our coach was saying, ‘Let’s see what you can do.’” Alex Johnson waited a long time to find out. As the saying goes, good things come to those who wait. Michael Madiol, junior:

If you develop the absolute sense of certainty that powerful beliefs provide, then you can get yourself to accomplish virtually anything, including those things that other people are certain are impossible. --William Lyon Phelps, American educator (1865–1943) The primary goal of every head coach is to instill “an absolute sense of certainty that powerful beliefs provide.” Every workout, every team retreat, every Tweet linking to an article on nutrition or sleep habits is about convincing our athletes about the validity of the plans we’ve drawn up and the value of our goals. How else can we get teenagers to forgo so many casual pleasures of high school, to commit to the pain and intensity of the Trial of Miles? Of course, a belief extends only as far as its first encounter with doubt. Michael Madiol learned that this season. A talented runner with a gift for the final straightaway, Madiol had glided through our program, arriving in big moments with a furious kick and an unblinking stare. Success seemingly came so easy for him that hesitation never seemed to cloud his gaze, and despite winning the F/S Conference 800 Meter Championship in Track, his coaches were still unsure they’d found his limits. Our limit, of course, is the faith we have in our own bodies. As long as we feel we can endure the pounding and fatigue, we charge on; any pull or tear that deviates from the ordinary, and we teeter on the brink of insecurity. A month ago, Michael began to feel a tug in the popliteal region of his knee. The muscle was hard to pinpoint, and the nature of the pain difficult to isolate. But it was a kink in his otherwise fluid motion. Suddenly, Michael Madiol had lost his absolute sense of certainty. What followed were weeks that mixed in differentiated workouts and rest, lineups that tried to spare him the pounding, race plans conceived to let him build towards success. There were days at a time where he felt like his old self, where he could almost forget the back of his knee. And then it would yank at him again, and Michael tumbled back to earth. The moment of crisis reached its apex in the Regional Race. After sitting out the Conference Meet, Michael returned to the lineup and resumed his habitual position in the heart of the chase pack. He finished 7th that day. The fear of injury had not abated, but his confidence in his toughness was fortified. By the time he took the line on Saturday, he again had the look of a man who could “accomplish virtually anything.” And so he did, running a 12 second PR on a day when we absolutely had to have it. This will not be the last time that Michael Madiol has doubts, nor will it be the last time we need him to step up. But when the time comes again, he can draw on the memory that when he was called to the fray, he plunged in without hesitation, undeterred by the fears pulling at the back of his mind or the pain lodged somewhere behind his knee. Danny Winek, senior: Danny Winek has been around running his whole life. The youngest of three Winek brothers, each who ran for Neuqua Valley, he joined the team in 2014, already decorated in amateur competitions. He has run all over the country, traveled to watch the Olympic Trials, spoken with world-class runners, and filled the split sheets with dizzying accomplishments. Unlike so many other elite performers in our program, Danny had never been anything BUT a distance runner, had never dallied in other sports before discovering his true calling. For Danny, there has only ever been the one true love. But that love often punished him. His light frame and powerful stride made him susceptible to injury, and in the past two years he has missed significant stretches with a variety of reactions and strains. Coming in to the summer, he had to build himself back up slowly, first running only a little at a time, then sliding into a few workouts here and there, then gradually working his mileage up to elite levels. He was never able to endure the pounding of workhorses like Ryan or Zach, but with careful guidance and a little luck, Danny made it through his senior campaign with relatively little time on the shelf. Of course, the pressure of good health can wear someone down as surely as heavy mileage. Having missed so much time, each race gained so much more significance for Danny. He only had one more Conference Meet, one more State series. Unlike Chris Keeley, there was no more next year as consolation for Danny Winek. He would have to be excellent this year, or live with the regret. For the last weeks of October, running grew less fun for Danny. Though he ran reasonably well at Regionals, he was 25th at Sectionals, well behind the pack. Despite his pedigree and ambition, it no longer felt as though he was in control of the story he had been trying to write, and he was running out of time to reassert himself. It’s hard to say what exactly allowed Danny to run almost a minute faster a week later. Perhaps it was the extra rest or a chance to step away from the pressures of college applications. Maybe it was the peace that comes right before the gunshot, the sudden acceptance that you are in this and there is no escaping it. But I believe the answer lies in the bus ride down, the long dinner with his teammates, the laughter that filled that hotel meeting room before bed. Danny is and always has been an elite runner. But he has never been alone. Danny was buoyed by his friendship with Tyler and Alex and Dakota, his respect for Chris and Zach and Michael. He—more than anyone—benefited from Ryan’s unselfish race. He was lifted, I like to believe, by the recognition that though the task was grim and weighty, the journey had truly been a joy. “Being deeply loved by someone gives you strength,” wrote the Chinese philosopher Laozi, “while loving someone gives you courage.” Danny could love running, but running could never love him back. For that, he needed a team. Ryan Kennedy, senior: More than most, Ryan Kennedy has defined himself by places and times. Even as a freshman, he was aware of the PRs of other notable freshmen in the state. He paid attention to his competitors, measured himself against them, and sought opportunities to ply himself against the best. This went for his teammates, too; despite an absurdly deep Varsity his sophomore year, Ryan pushed himself to match paces with Austin Kinne, Aidan Livingston, and Dominick Dina. He never took his eye off the leaderboard, looking for advantage in extra workouts or weekend form corrections. By the time he was a senior, the team had taken on his persona, and Ryan, more than even Zach, was the engine of excellence. His body had finally matured to the point that it could respond to his expectations, and Ryan approached every race with a furious determination that bordered on violence. He didn’t just want to win; he wanted to dominate. And so he did. He finished 2nd at Hornet-Red Devil, 19th at Richard Springs, 6th at Twilight, 4th at Conference, 2nd at Regionals, 4th at Sectionals. He broke up packs, chased down front-runners, and outkicked athletes with more established pedigrees. Other teams feared and planned around him; Wheaton-Warrenville South’s Conference strategy keyed off Ryan’s race. But for State, we asked something more of Ryan. We asked him to hold back. Ryan’s whole strategy all year had been simply to go; now, we needed him to restrain himself. Instead of positioning himself amidst the pack of all-state potentials, Ryan would have to chase them down. The plan unfolded perfectly through the first mile, with Ryan sacrificing 5-7 seconds to pace the pack into the trapezoid. As they began to move up, Ryan and Danny created some separation, accelerating together. It was a huge confidence boost for Danny, who had run below his own standards the previous two weeks. He ended up running a PR, dipping below 15:00 for the first time, finishing 3rd for our team to solidify our finish. Ryan, meanwhile, picked up nearly two dozen places in the last mile. Yet when he staggered out of the chute afterwards, it was clear he was unsatisfied. He had finished eight spots out of All-State, a North Star goal that had guided him through innumerable periods of doubt. It had been there for him; he could feel it. Instead, he had sacrificed for the team. As the scores were finally confirmed, the significance of Ryan’s forfeiture became obvious. Danny, Michael, Alex, and Tyler each ran their gutsiest race of the season. We narrowly outdueled a primed Wheaton-Warrenville South. As Thomas Stevenson soon tweeted: Sometime in the future on a Friday at the team dinner in Peoria @PVsteen will tell the story of Ryan Kennedy and the 22 places he gained in the last mile to secure the trophy. He’s right. Ryan lost his bid for All State. In return, he gained something far more valuable: a legend. Zach Kinne, junior: One afternoon as a lark, we looked up the qualities identified by clinical psychologists that best describe human genius. In the late 1970s, a researcher named Dr. Alfred Barrious compiled a list of 24 traits most often associated with genius, including Drive, Courage, Devotion to Goals, Knowledge, Honesty, Optimism, Enthusiasm, Willingness to Take Chances, Dynamic Energy, Enterprise, Patience, and Perfectionism. Reading the list aloud, we stopped laughing. Most of the qualities perfectly described Zach Kinne. Drive? Courage? Devotion to Goals? That’s Zach. Willingness to take chances? You don’t put yourself in the lead chase pack at State without that gambler’s mentality. He takes no short cuts. If given a choice between rest and packing in extra miles, he chooses the miles every time. He is boundlessly positive, ruthlessly candid, and supremely confident. He even has a good sense of humor. The most telling quality of genius is the effortlessness with which it performs excellence. True genius makes the inconceivable seem natural, even humdrum. Yet it would be a mistake to claim that Zach went unchallenged this year, that his mind never entertained doubts. The week of Twilight, he forfeited sleep to keep up with his studies and relationships. He subsequently contracted a respiratory infection. When it came time to race, Zach—who was favored—found himself in a dogfight with fellow junior Thomas Shilgalis. Zach tried to gap him at the 2; Thomas kept pace. Zach tried to lose him under the bleachers, but by then Thomas thought he could win. When they hit the track, Zach dipped into his reserves, hoping to find a kick. But what he came up with was no match for the Redhawk. On that night, it was Shilgalis that made it look easy. But Zach was undeterred. He secured some antibiotics, restructured his rest, and kept to his routine. Though he believes he can run with anyone, he agreed to a conservative race plan that put him in a position where he could save something for the final stretch. One of the more stunning sights from Saturday’s meet was Zach Kinne kicking down competitors, elite runners with more feared straightaway bursts. Yet Zach had prepared for the moment; he made it look as straightforward as taking off a pair of socks. And that is what makes Zach Kinne such a special athlete. He makes others believe that there is truly nothing he cannot do in a mile. He will adapt to any strategy, adjust to any pace, and just when you think he’s reached his ceiling, he’ll slip through a skylight and soar. As for the future, it’s hard to say what awaits him in Track or Cross Country. After all, if everyone could see it coming, it wouldn’t be genius. Epilogue: Perhaps the best thing about our sport is how relatively commonplace these stories are. Every runner who laced up on Saturday, regardless of gender or division, weathered a prolonged siege from doubt, tore through the fracas, and emerged from the chute, spent yet standing. Wheaton Warrenville South answered questions about their youth; Downers Grove North proved that, if anything, they were underrated all season. And pity poor Danny Kilrea, who wasn’t just pursued by an entire state, but 40 years of Detweiller ghosts. Our season ended in triumph, but it could have just as easily gone another way. A little less luck, a little more hesitancy, and we may have endured a quiet bus ride home, lamenting our spent fortunes and missed opportunities. Every runner knows with grudging certainty that good intentions and careful preparation are no guarantee, and as surely as Zach Kinne triumphed, in another race he might have ended up in the mud like Chris Keeley. It is this insecurity, this sense of illegitimacy that hounds so many into never trying in the first place. The halls of every high school overflow with never-gonna-try runners undone before the race even starts. True greatness, then, is not the place or the time or the trophy. It is the courage to stand against doubt and resist. “The beginning of wisdom is found in doubting,” wrote the medieval philosopher Pierre Abelard. “By doubting, we come to the question, and by seeking we may come upon the truth.” So be it. We answered the question on Saturday. We found out the truth about ourselves. As we drove home in the darkness, we passed through a section of road construction. One of the seniors pointed out a traffic pylon, and the bus redoubled with laughter as the story came out once again. The stolen cone. The mad pursuit. Thieves in the night. But in the end, nothing was stolen. They earned everything they got. |

News Categories

All

Archives

August 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed